Relative Extent, Relative Risk and Attributable Risk

Assessing the Relationship Between Key Stressors and Biological Conditions: Relative Extent, Relative Risk and Attributable Risk

Overview

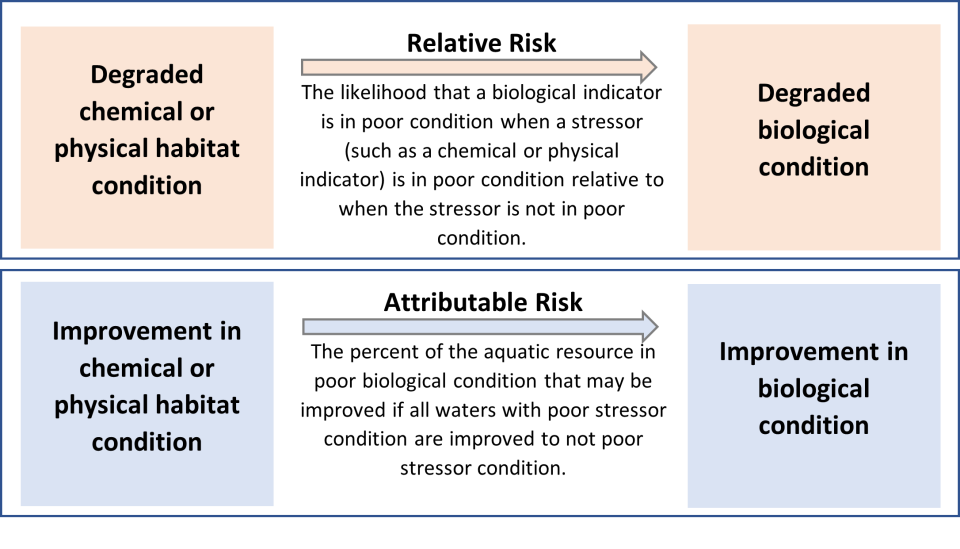

The National Aquatic Resource Surveys (NARS) provide data to support the protection and restoration of our nation’s water, including their ecological function. This includes estimating the benefits that might be derived if key stressors were reduced. For this analysis, NARS analysts evaluate chemical and physical indicators in relation to biological condition. The indicators, i.e., stressors, can negatively affect the biological condition of aquatic organisms or communities. Figure 1 illustrates how analysts examine the relationship between stressors and poor biological conditions.

Analysts use three approaches to rank stressors as they apply to biological indicators. The first approach, relative extent, looks at how many lakes, rivers/streams miles, wetland area, or coastal water area are in poor condition for selected chemical and physical indicators, e.g., what percent of our waters have excess phosphorus concentrations. The second, relative risk, examines the severity of the impact from an individual stressor when it is present, e.g., how likely is biology to be degraded when phosphorus levels are high compared to when lower levels of phosphorus are present. This is like what your doctor tells you about your risk of heart disease if you smoke compared to if you don’t smoke. The third approach involves attributable risk calculation, which is a value derived by combining the first two risk values into a single number. The higher the attributable risk, the more improvement is possible if the stressor is reduced. In the human health field, it is similar to what we would say about the reduction in heart disease the U.S. would experience if smoking was eliminated. Resource managers use the attributable risk values to rank the severity of different stressors and to prioritize management actions.

These risk analysis tools are intended to help guide management priorities, not to establish a direct cause and effect connection. More details on these approaches are described below. Results from the most recent analyses can be found in NARS reports and the rivers/streams dashboard, lakes dashboard, and wetlands dashboard. See the reference section for additional reading.

Figure 1:

Relative Extent

Water resource managers need to consider how extensive a stressor is when setting priority actions at national, regional, and state scales. Relative extent compares the percent of waters rated poor for each individual stressor. Most stressors can be found in all geographic areas, but those that are not pervasive do not have high relative extents.

Relative Risk

Relative risk is a way to examine the severity of the impact of a stressor when it occurs. Relative risk is used frequently in the human health field. John Van Sickle et al. (2006) adapted a risk assessment approach to allow its use with survey data to quantify the relative risk from multiple indicators of stress (hereafter, stressors) for wadeable streams in the mid-Atlantic. They borrowed the relative risk terminology from medical epidemiology because most people are familiar with the concept as it relates to human health (e.g., a greater risk of developing heart disease if one has high cholesterol levels). Relative risk results are presented in terms of a relative risk ratio. “For example, the relative risk for colorectal cancer is 2.24 if one first-degree relative had the disease and 3.97 if more than one first-degree relative had the disease (American Cancer Society 2017; Butterworth, Higgins, and Pharoah 2006). In other words, if you have a strong family history of the disease, you are four times more likely to get it than a person with no family history” (Herlihy et al. 2019).

Similarly, scientists can examine the likelihood of finding poor biological conditions in waterbodies when stressors, such as excess phosphorus or poor habitat, are high relative to the likelihood when they are low. When these two likelihoods are quantified, their ratio is called the relative risk. A relative risk value of 1 means that poor biological conditions are just as likely when the stressor is rated poor as when it is rated good or fair — in essence, no demonstrable effect. A relative risk of 2, however, means poor biological conditions are twice as likely when a stressor is in poor condition than they are when the stressor is not in poor condition. Further information is given by Lachin (2000).

Attributable Risk

Attributable risk represents the magnitude or importance of a potential stressor and can be used to help rank and set priorities for policymakers and managers. Attributable risk is derived by combining relative extent and relative risk into a single number for ranking purposes. Conceptually, attributable risk provides an estimate of the proportion of poor biological conditions that could be reduced if high levels of a particular stressor were reduced (John Van Sickle and Paulsen 2008; J. Van Sickle 2013). This number is presented in terms of the amount in poor biological condition that could be improved — that is, moved from poor into either good or fair condition categories. “The calculation of attributable risk makes three major assumptions involving causality (the stressor causes an increased probability of poor condition); reversibility (if the stressor is eliminated, causal effects will also be eliminated); and independence (stressors are independent of each other). A highly desirable feature of attributable risk is that it combines estimated stressor extent with relative risk into a single index to permit ranking the evaluated stressor indicators by the degree of their potential impact on the total resource” (Herlihy et al. 2019).

Attributable risk is not intended as an absolute “prediction” of the improvement in biological condition but rather an estimate calculated in a consistent manner for each stressor so that they can be ranked relative to one another. Use of the attributable risk information can help policymakers and resource managers prioritize actions and the use of limited resources by stressor and geographic area.

Further information on attributable risk is given by Benichou (2001), Cox (1985), Gefeller (1992), Fleiss (1979), Uter and Pfahlberg (1999), and Walter (1976).

Calculations

For more information on how analysts calculate Relative Extent, Relative Risk and Attributable Risk for NARS, see the see the calculations in this document as well as the survey reports and Technical Support Documents (USEPA 2016c, 2016d, 2016b, 2016e, 2016a, 2017, 2020a, 2020b).

Citations and other References

American Cancer Society. 2017. “Colorectal Cancer Facts & Figures 2017-2019.” Report. Atlanta: American Cancer Society.

Herlihy, A. T., S. G. Paulsen, M. E. Kentula, T. K. Magee, A. M. Nahlik, and G. A. Lomnicky. 2019. “Assessing the Relative and Attributable Risk of Stressors to Wetland Condition Across the Conterminous United States.” Journal Article. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment. Vol. 191(Suppl 1). https://doi.org/doi.org/10.1007/s10661-019-7313-7.

USEPA. 2016a. “National Lakes Assessment 2012: A Collaborative Survey of Lakes in the United States.” Report EPA 841-R-16-113. US Environmental Protection Agency.

USEPA. “National Rivers and Streams Assessment 2008-2009: A Collaborative Survey.” Report EPA-841-R-16-007. US Environmental Protection Agency.

USEPA. 2016c. “National Wetland Condition Assessment: 2011 Technical Report.” Report EPA-843-R-15-006. US Environmental Protection Agency.

USEPA. 2016d. “National Wetland Condition Assessment: A Collaborative Survey of the Nation’s Wetlands.” Report EPA-843-R-15-005. US Environmental Protection Agency.

USEPA. 2016e. “Office of Water and Office of Research and Development. National Rivers and Streams Assessment 2008-2009 Technical Report.” Report EPA/841/R-16/008. US Environmental Protection Agency. http://www.epa.gov/national-aquatic-resource-surveys/nrsa.

USEPA “National Lakes Assessment 2012: Technical Report.” Report EPA 841-R-16-114. US Environmental Protection Agency. https://www.epa.gov/national-aquatic-resource-surveys/nla.

USEPA. 2020a. “National Aquatic Resource Surveys. National Rivers and Streams Assessment 2013–2014. (Data and Metadata Files).” Report. US Environmental Protection Agency. http://www.epa.gov/national-aquatic-resource-surveys/data-national-aquatic-resource-surveys.

USEPA. 2020b. “National Rivers and Streams Assessment 2013-2014 Technical Support Document.” Report EPA 843-R-19-001. US Environmental Protection Agency. https://www.epa.gov/national-aquatic-resource-surveys/nrsa.

Van Sickle, John, and Steven P. Paulsen. 2008. “Assessing the Attributable Risks, Relative Risks, and Regional Extents of Aquatic Stressors.” Journal Article. Journal of the North American Benthological Society 27 (4): 920–31. https://doi.org/10.1899/07-152.1.

Van Sickle, John, John L. Stoddard, Steven P. Paulsen, and Anthony R. Olsen. 2006. “Using Relative Risk to Compare the Effects of Aquatic Stressors at a Regional Scale.” Journal Article. Environmental Management 38: 1020–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-005-0240-0.