Anaerobic Digestion on Swine Farms

On this page:

- Where Swine Farms Are Located

- Current Manure Management Practices

- Current Use of Anaerobic Digestion Systems

- Project Development Trends

- Barriers

- Solutions

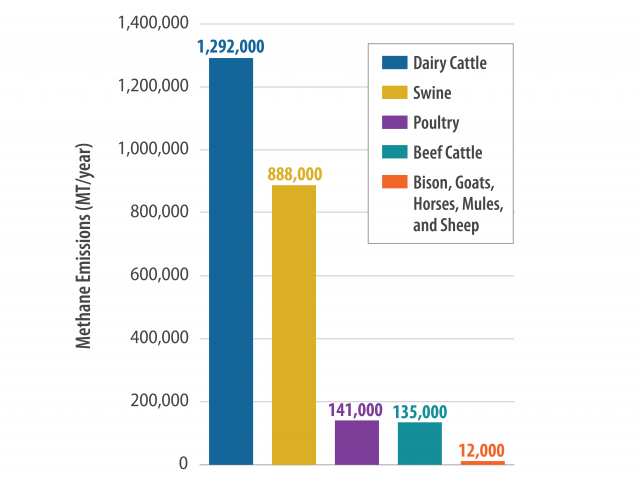

Anaerobic digestion (AD) of swine manure in the United States (U.S.) has many environmental and economic benefits, including producing renewable energy and reducing greenhouse gas emissions, and is underutilized as a manure treatment option. Swine manure is the nation’s second largest source of methane from livestock manure management (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Total Manure Management Methane Emissions in the U.S., 2018

As of April 2021, there were 45 known AD systems accepting swine manure in the U.S., and these systems reduce approximately 650,000 MT CO2e each year.1 However, there is much more potential to expand AD capacity. The AgSTAR program, a collaborative effort of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), estimates that there is potential for AD systems on approximately 5,400 additional swine farms, with the potential to reduce 20,800,000 MT CO2e each year.2 That’s equivalent to planting nearly 350 million trees!3

Where Swine Farms Are Located

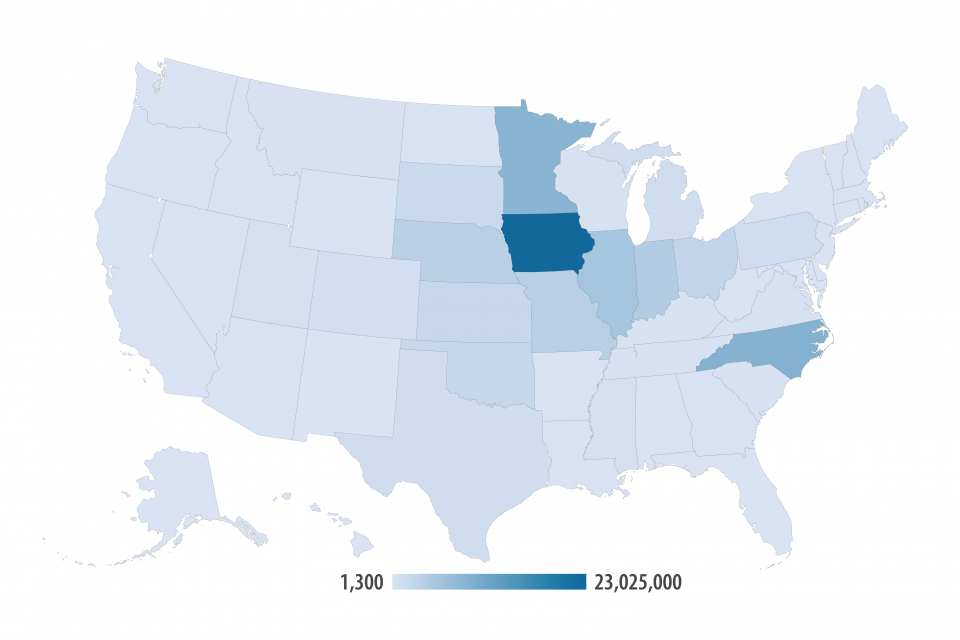

Figure 2. U.S. Swine Population, 2018

U.S. swine populations are concentrated mainly in the Midwest and Southeast, with the majority (over 55 percent) of hogs located in Iowa, Minnesota, and North Carolina. Illinois, Indiana, Missouri, and Nebraska are the next most populous states for hogs. Figure 2 shows the U.S. swine population distribution.

Current Manure Management Practices

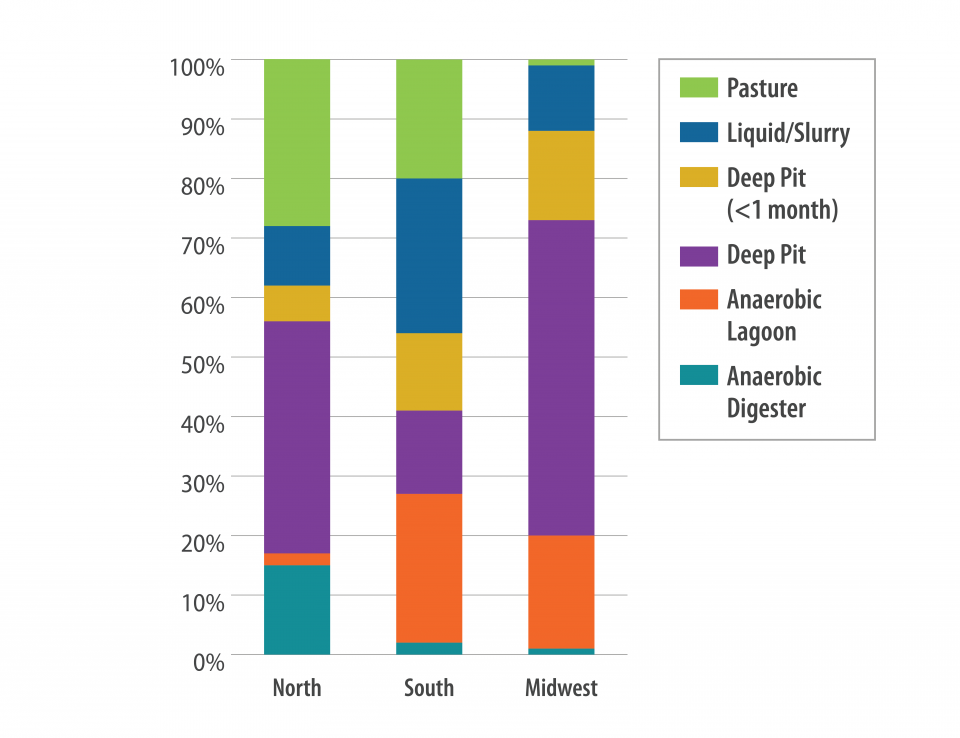

Practices for handling swine manure vary by region. Swine farms in some Midwest states, for example, typically use deep pit storage, which allows manure to drop into storage pits underneath slatted floors of the barn. Manure is pumped out once or twice a year and is land applied as fertilizer. Some digestion of manure does occur in the pits, resulting in odor issues and the release of methane into the atmosphere. Some operations send vented air from barns through a bio-filter (i.e., a bed of activated media such as wood chips) for odor control. However, due to the infrequent removal of manure, operations using deep pit storage must modify manure management processes and structures to incorporate AD systems.

Flush collection, in which flowing water is used to remove manure, is another common manure management practice, particularly in North Carolina. The collected dilute flushed manure has traditionally been stored in outdoor uncovered lagoons. To make AD a more economical option, hog farmers may switch to scrape collection, thus reducing the size of the AD system needed and increasing the biogas production per gallon input potential.

Figure 3 presents the most common types of manure management on swine farms in the U.S. For more information about manure management system types, see Chapter 9 of the USDA Agricultural Waste Management Field Handbook (pdf) or visit the Livestock and Poultry Environmental Learning Center’s Manure Collection and Handling Systems site.

Current Use of Anaerobic Digestion Systems

Figure 3. Manure Management Practices on Swine Farms in the U.S., 2018

Covered lagoons are the most popular type of AD system for swine operations, currently processing manure from nearly 400,000 hogs at over 20 AD sites.4 Some of these sites encompass multiple covered lagoons at adjacent farms, which send collected biogas to a centralized location for processing and use.

Complete mix systems are the second most common AD system currently in use for swine manure. There are about 18 of these systems operating in the U.S., accepting manure from around 160,000 head of swine.5 Complete mix systems are primarily located at smaller, single-farm operations in the Midwest.

Covered lagoons and complete mix systems are typically the best AD technologies to treat swine manure because of the dilute nature of flushed swine manure.

Project Development Trends

Over the last few decades, the pork industry has evolved from a predominantly open market system of independent producers who grow and market their own hogs to a model where large companies, often referred to as integrators, provide pigs or breeding stock under a contract to growers who house and manage the pigs.

Due to the increasingly integrated nature of the industry, most recent AD projects in the swine sector have been developed through partnerships between integrators and project developers, as well as utilities and other stakeholders. For example, Smithfield Foods and Dominion Energy developed a multiple-farm AD project in Utah that began generating renewable natural gas (RNG) at the end of 2020. This project includes a network of 26 individual but adjacent swine farms that raise hogs under contract with Smithfield. Methane captured from covered lagoons is sent to a centralized location, purified, and injected into an existing natural gas distribution system to serve homes, businesses, power plants, and other natural gas consumers. The companies’ joint venture, Align RNG, also has similar projects under development in North Carolina and Virginia. Smithfield has also partnered with Roeslein Alternative Energy on an RNG project in Missouri.

New and existing AD systems across the country are undergoing a distinct shift in biogas use, from electricity generation to RNG production. This is primarily due to economic factors, as discussed below.

Barriers

AD remains an uncommon manure management practice in the swine industry mainly due to economic challenges. In addition to the cost of the digester, most swine manure storage and management practices cannot be adapted to AD without significant changes. For instance, adding a digester to a deep pit system in the Midwest would require additional structures, as well as a change in operational practices. These changes require significant capital investment. Hiring additional staff to operate the AD system and meeting additional regulatory or permitting requirements may also be costly.

Individual growers typically have narrow profit margins, which means they are less likely to invest in practices beyond what is needed for the farm to function. A farmer may be aware of the benefits of AD, but if the cost is perceived to outweigh those benefits, there is limited incentive to pursue AD. Benefits such as environmental stewardship, odor reduction, and emission reductions are difficult to monetize, and revenue from electricity generation, although a potential source of direct income for a farm with an AD system, is often not high enough to make up the deficit. Electricity prices are generally low in areas where swine growers are located, and these facilities don’t require enough power to recuperate significant value from on-site use of generated electricity.

Solutions

The most effective way to address economic barriers is to increase project revenue and cost savings. Considerations for increasing revenue or cost savings include:

- Market incentives for biogas. Tax credits, renewable energy credits, carbon offset credits, or other incentives offered through federal or state renewable or low carbon fuel standards are a potential source of revenue or cost savings. Several states have created programs focused on the reduction of fossil fuel-based fuel, such as Low Carbon Fuel Standard (LCFS) incentive programs in California and Oregon. At the federal level, the Renewable Fuel Standard provides market-based monetary value for renewable fuels, including RNG.

Market trends for renewable/low carbon fuels have made RNG more valuable than electricity. If a project can demonstrate that RNG is used as transportation fuel and meets appropriate requirements, RNG can also generate Renewable Identification Numbers or LCFS credits. Because of this, most swine projects currently in development have plans to produce RNG. - Strategic Partnerships. Many companies and utilities are willing to pay a premium for renewable energy or carbon offsets to reduce their carbon footprint. Biogas producers that partner with an organization to purchase the gas could potentially achieve greater revenues. Google, for example, helped pay for a portion of Loyd Ray (pdf) Farms AD operation and maintenance costs for carbon credits.

- Third party build/own/operate models. These models can relieve the grower of financial risk, as well as operational and maintenance responsibilities, while still providing the grower benefits like odor reduction and improved public image. Hub-and-spoke business models take advantage of economies of scale by using a centralized AD system or biogas upgrading facility for multiple farms, like the Smithfield projects noted above.

- Codigestion. Depending on the AD system, food waste or other organics may be codigested with swine manure to increase biogas production rates, which can increase revenue from energy sales. Charging a tipping fee for the disposal of other parties’ wastes is another source of income. Remley Farms, in Pennsylvania, digests up to 9,000 gallons of hog manure along with 2,000-3,000 gallons of food waste each day. The addition of food waste doubles the system’s electricity output.

- Nutrient concentration. Where technically feasible, creating other products such as concentrated nutrient fertilizers add to revenues or directly reduces costs of nutrient management. Storms Farm in North Carolina, for example, manages excess phosphorus from its 28,000 hogs using the swine industry’s first full-scale dedicated phosphorus recovery system, which captures 90 percent of the farm’s phosphorus and converts it to a condensed, stackable product that can be easily transported off-site. The high recovery rate is possible in large part because the farm uses a mixed plug flow digester.

- Federal, state, or local funding and streamlined permitting. Federal, state, or local direct financial assistance for feasibility studies and/or up-front costs can reduce financial barriers to implementing sustainable practices. The Project Planning and Financing page on the AgSTAR website includes a table of resources to help identify funding opportunities. Additionally, streamlining permitting processes can reduce project costs and expedite development of projects.

1AgSTAR Anaerobic Digester Database. This value includes direct methane reductions from the manure emissions as well as indirect reductions from the avoided use of fossil fuels.

2Market Opportunities for Biogas Recovery Systems at U.S. Livestock Facilities (pdf) report.

3Greenhouse Gas Equivalencies Calculator.

4AgSTAR Anaerobic Digester Database.

5AgSTAR Anaerobic Digester Database.