Climate Change Indicators: Heat Waves

This indicator describes trends in multi-day extreme heat events across the United States.

Key Points

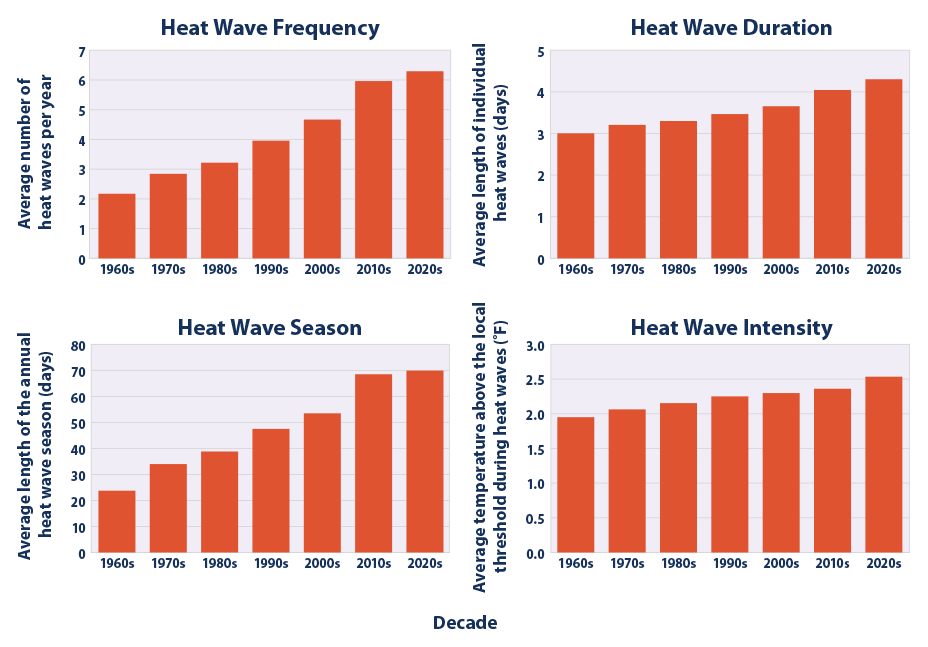

- Heat waves are occurring more often than they used to in major cities across the United States. Their frequency has increased steadily, from an average of two heat waves per year during the 1960s to six per year during the 2010s and 2020s (Figure 1).

- In recent years, the average heat wave in major U.S. urban areas has been about four days long. This is about a day longer than the average heat wave in the 1960s (Figure 1).

- The average heat wave season across the 50 cities in this indicator is about 46 days longer now than it was in the 1960s (Figure 1). Timing can matter, as heat waves that occur earlier in the spring or later in the fall can catch people off-guard and increase exposure to the health risks associated with heat waves.

- Heat waves have become more intense over time. During the 1960s, the average heat wave across the 50 cities in Figures 1 and 2 was 2.0°F above the local 85th percentile threshold. During the 2020s, the average heat wave has been 2.5°F above the local threshold (Figure 1).

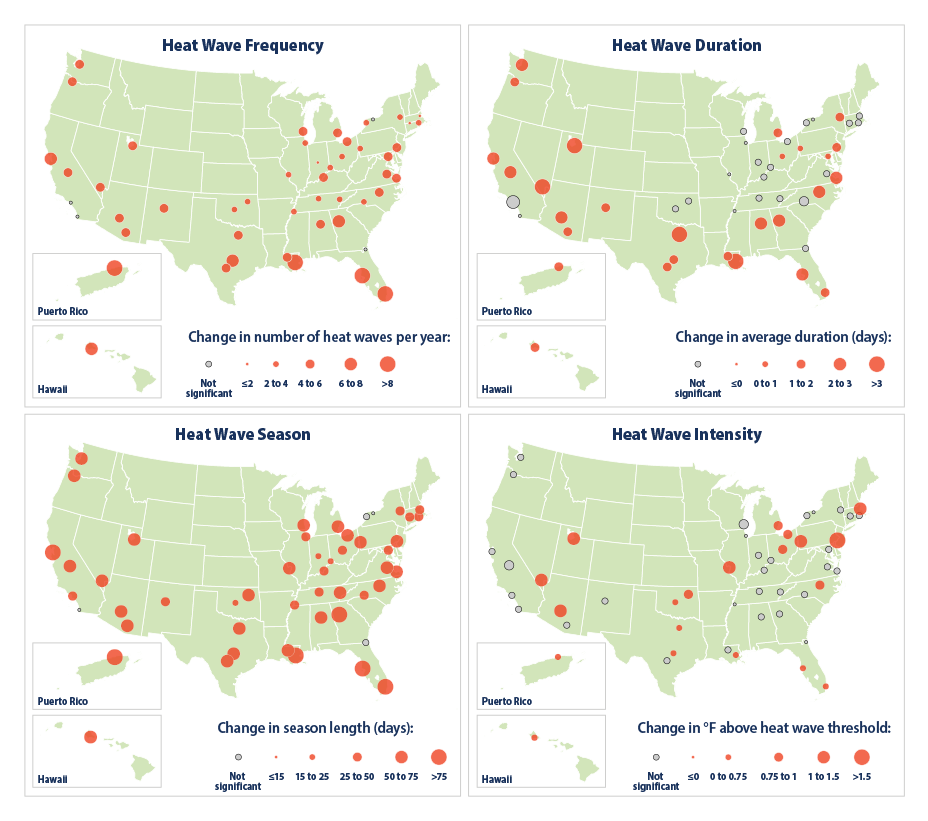

- Of the 50 metropolitan areas in this indicator, 46 experienced a statistically significant increase in heat wave frequency between the 1960s and 2020s. Heat wave duration has increased significantly in 28 of these locations, the length of the heat wave season in 46, and intensity in 20 (Figure 2).

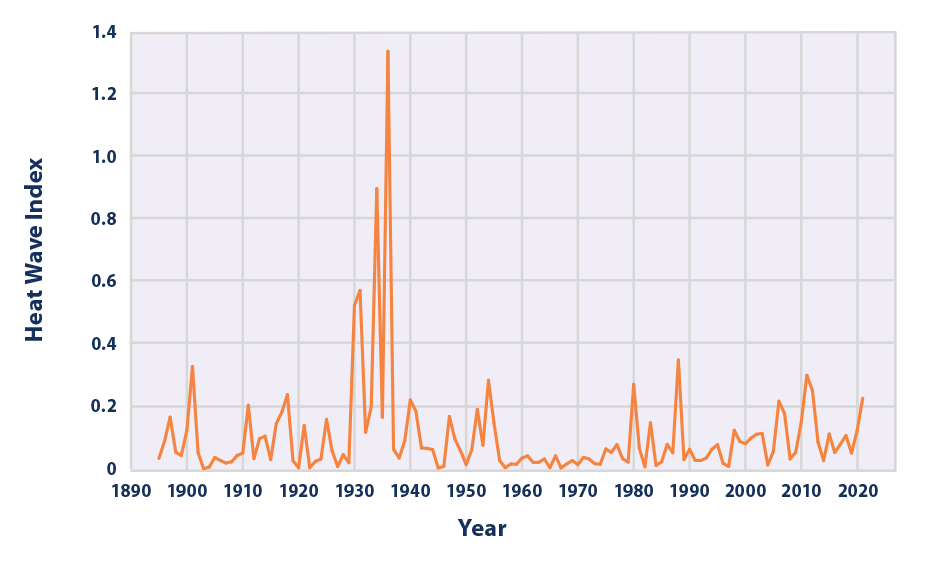

- Longer-term records show that heat waves in the 1930s remain the most severe in recorded U.S. history (Figure 3). The spike in Figure 3 reflects extreme, persistent heat waves in the Great Plains region during a period known as the “Dust Bowl.” Poor land use practices and many years of intense drought contributed to these heat waves by depleting soil moisture and reducing the moderating effects of evaporation.5

Background

A persistent period of unusually hot days is referred to as an extreme heat event or a heat wave. Heat waves are more than just uncomfortable: they can lead to illness and death, particularly among older adults, the very young, and other vulnerable populations (see the Heat-Related Deaths and Heat-Related Illnesses indicators).1 Prolonged exposure to excessive heat can lead to other impacts as well—for example, damaging crops, injuring or killing livestock, and increasing the risk of wildfires. Prolonged periods of extreme heat can lead to power outages as heavy demands for air conditioning strain the power grid.

Unusually hot days and heat wave events are a natural part of day-to-day variation in weather. As the Earth’s climate warms, however, hotter-than-usual days and nights are becoming more common (see the High and Low Temperatures indicator) and heat waves are expected to last longer and become more frequent and intense.2 Increases in these extreme heat events can lead to more heat-related illnesses and deaths, especially if people and communities do not take steps to adapt.3 Even small increases in extreme heat can result in increased deaths and illnesses.4

About the Indicator

This indicator examines trends over time in four key characteristics of heat waves in the United States:

- Frequency: the number of heat waves that occur every year.

- Duration: the length of each individual heat wave, in days.

- Season length: the number of days between the first heat wave of the year and the last.

- Intensity: how hot it is during the heat wave.

Heat waves can be defined in many different ways. For consistency across the country, Figures 1 and 2 define a heat wave as a period of two or more consecutive days when the daily minimum apparent temperature (the actual temperature adjusted for humidity) in a particular city exceeds the 85th percentile of historical July and August temperatures (1981–2010) for that city. EPA chose this definition for several reasons:

- The most serious health impacts of a heat wave are often associated with high temperatures at night, which is usually the daily minimum.4 The human body needs to cool off at night, especially after a hot day. If the air stays too warm at night, the body faces extra strain as the heart pumps harder to try to regulate body temperature.

- Adjusting for humidity is important because when humidity is high, water does not evaporate as easily, so it is harder for the human body to cool off by sweating. That is why health warnings about extreme heat are often based on the “heat index,” which combines temperature and humidity.

- The 85th percentile of July and August temperatures equates to the nine hottest days during the hottest two months of the year. A temperature that is typically only recorded nine times during the hottest part of the year is rare enough that most people would consider it to be unusually hot.

- By using the 85th percentile for each individual city, Figures 1 and 2 define “unusual” in terms of local conditions. After all, a specific temperature like 95°F might be unusually hot in one city but perfectly normal in another. Plus, people in relatively warm regions (such as the Southwest) may be better acclimated and adapted to hot weather.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) calculated apparent temperature for this indicator based on temperature and humidity measurements from long-term weather stations, which are generally located at airports. Figures 1 and 2 focus on the 50 most populous U.S. metropolitan areas that have recorded weather data from a consistent location without many missing days over the time period examined. The year 1961 was chosen as the starting point because most major cities have collected consistent data since at least that time.

Figure 3 provides another perspective to gauge the size and frequency of prolonged heat wave events. It shows the U.S. Annual Heat Wave Index, which tracks the occurrence of heat wave conditions across the contiguous 48 states from 1895 to 2021. This index defines a heat wave as a period lasting at least four days with an average temperature that would only be expected to persist over four days once every 10 years, based on the historical record. The index value for a given year depends on how often such severe heat waves occur and how widespread they are.

About the Data

Indicator Notes

As cities develop, vegetation is often lost, and more surfaces are paved or covered with buildings. This type of development can lead to higher temperatures—part of an effect called an “urban heat island.” Compared with surrounding rural areas, built-up areas have higher temperatures, especially at night.8 Urban growth since 1961 may have contributed to part of the increase in heat waves that Figures 1 and 2 show for certain cities. This indicator does not attempt to adjust for the effects of development in metropolitan areas, because it focuses on the temperatures to which people are actually exposed, regardless of whether the trends reflect a combination of climate change and other factors.

Figures 1 and 2 focus on the 50 most populous metropolitan areas that had complete data for the entire period from 1961 to 2023. Several large metropolitan areas did not have enough data, such as New York City, Houston, Minneapolis–St. Paul, and Denver. In some of these cases, the best available long-term weather station was relocated sometime between 1961 and 2023—for example, when a new airport opened.

As noted above, Figures 1 and 2 focus on daily minimum temperatures because of the connection between nighttime cooling (or lack thereof) and human health. For reference, EPA’s technical documentation for this indicator shows the results of a similar analysis based on daily maximum temperatures.

Temperature data are less certain for the early part of the 20th century because fewer stations were operating at that time. In addition, measuring devices and methods have changed over time, and some stations have moved. The data in Figure 3 have been adjusted to the extent possible to account for some of these influences and biases, however, and these uncertainties are not sufficient to change the fundamental nature of the trends.

Data Sources

Figures 1 and 2 are adapted from an analysis by Habeeb et al. (2015).9 They are based on temperature and humidity measurements from weather stations managed by NOAA’s National Weather Service. NOAA’s National Centers for Environmental Information compiled and provided the data.

Figure 3 is based on measurements from weather stations in the National Weather Service Cooperative Observer Network. The data are available online at: www.ncei.noaa.gov. Components of this indicator can also be found at: www.globalchange.gov/indicators.

Technical Documentation

References

1 Hayden, M. H., Schramm, P. J., Beard, C. B., Bell, J. E., Bernstein, A. S., Bieniek-Tobasco, A., Cooley, N., Diuk-Wasser, M., Dorsey, M. K., Ebi, K., Ernst, K. C., Gorris, M. E., Howe, P. D., Khan, A. S., Lefthand-Begay, C., Maldonado, J., Saha, S., Shafiei, F., Vaidyanathan, A., & Wilhelmi, O. V. (2023). Chapter 15: Human health. In USGCRP (U.S. Global Change Research Program), Fifth National Climate Assessment. https://doi.org/10.7930/NCA5.2023.CH15

2 Marvel, K., Su, W., Delgado, R., Aarons, S., Chatterjee, A., Garcia, M. E., Hausfather, Z., Hayhoe, K., Hence, D. A., Jewett, E. B., Robel, A., Singh, D., Tripati, A., & Vose, R. S. (2023). Chapter 2: Climate trends. In USGCRP (U.S. Global Change Research Program), Fifth National Climate Assessment. https://doi.org/10.7930/NCA5.2023.CH2

3 U.S. EPA (Environmental Protection Agency). (2015). Climate change in the United States: Benefits of global action (EPA 430-R-15-001). www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2015-06/documents/cirareport.pdf

4 Sarofim, M. C., Saha, S., Hawkins, M. D., Mills, D. M., Hess, J., Horton, R., Kinney, P., Schwartz, J., & St. Juliana, A. (2016). Chapter 2: Temperature-related death and illness. In USGCRP (U.S. Global Change Research Program), The impacts of climate change on human health in the United States: A scientific assessment (pp. 43–69). http://dx.doi.org/10.7930/J0MG7MDX

5 CCSP (U.S. Climate Change Science Program). (2008). Synthesis and Assessment Product 3.3: Weather and climate extremes in a changing climate. www.globalchange.gov/browse/reports/sap-33-weather-and-climate-extremes-changing-climate

6 NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration). (2024). Heat stress datasets and documentation (provided to EPA by NOAA in April 2024) [Data set].

7 Kunkel, K. (2022). Updated version of Figure 2.3 in: CCSP (U.S. Climate Change Science Program). (2008). Synthesis and Assessment Product 3.3: Weather and climate extremes in a changing climate. www.globalchange.gov/browse/reports/sap-33-weather-and-climate-extremes-changing-climate

8 U.S. EPA (Environmental Protection Agency). (2016). Heat island effect. www.epa.gov/heat-islands

9 Habeeb, D., Vargo, J., & Stone, B., Jr. (2015). Rising heat wave trends in large US cities. Natural Hazards, 76(3), 1651–1665. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-014-1563-z