Chemours Washington Works History and Safe Drinking Water Act (SWDA) Settlements

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, collectively called “PFAS,” are a group of man-made chemicals that have been manufactured and used in industry and consumer products since the 1940s. There are thousands of different PFAS chemicals, some of which have been more widely used and studied than others.

For more information, please visit EPA’s PFAS website.

On this page

- Washington Works History

- EPA SDWA Actions at Washington Works

- Current Sampling Results for PFOA

- Historic Sampling Results for PFOA

- PFAS Pathways

- Evolving PFAS Research and Health Impacts

Washington Works History

The Washington Works Facility, formerly owned by E. I. du Pont de Nemours and Company, Incorporated (“DuPont”) and currently owned by The Chemours Company (“Chemours”), is located in Washington, West Virginia. The Facility historically used manufacturing processes with perfluorooctanoic acid (“PFOA” or “C-8”) and hexafluoropropylene oxide dimer acid (“HFPO-DA”) under the trade name “GenX.” Residues containing PFAS generated by the Facility have been released into the environment at and around the Facility. Studies have found that PFAS is highly persistent in the environment with little or no degradation occurring in air, water, or soil.

EPA SDWA Actions at Washington Works

In response to concerns over DuPont’s use of PFAS, from the 1990s to early 2000s, DuPont performed voluntary water sampling to detect the presence and level of PFOA in and around certain DuPont facilities in West Virginia. As a result of DuPont’s sampling, PFOA was detected in varying concentrations in and around certain DuPont facilities in West Virginia, including private drinking water wells and public water supplies.

In 2001, the West Virginia Department of Environmental Protection (“WVDEP”) entered into a consent order with DuPont, which established a C-8 Assessment of Toxicity Team (“CAT Team”) that later determined a screening level of 150 parts per billion (“ppb”) for the Washington Works Facility.

In March 2002, EPA and DuPont entered into an Emergency Administrative Order under the Safe Drinking Water Act (“SDWA”) (“2002 Order”) in which DuPont agreed to provide alternative drinking water or treatment for public and private water users living near the Washington Works Facility if the level of PFOA detected in their drinking water was greater than the PFOA screening level of 150 ppb, established by the CAT Team.

In November 2006, after science on health effects of PFOA evolved, EPA entered into a second Emergency Administrative Order (“2006 Order”) that replaced the 2002 Order and established a site-specific action level equal to or greater than 0.50 ppb. As a result, DuPont was required to offer alternate water or treatment to private water systems with data demonstrating PFOA levels greater than 0.50 ppb.

In 2009, EPA established a provisional health advisory for PFOA of 400 parts per trillion (“ppt”) or 0.40 ppb to address short-term exposure to PFOA. In March 2009, EPA then entered into a third Emergency Administrative Order (“2009 Order”) with DuPont that replaced the 2006 Order and lowered the allowable concentration of PFOA in drinking water from 0.50 ppb to 0.40 ppb in communities near the Facility. The provisional health advisory for PFOA was based on available evidence at that time.

In 2016, EPA established a lifetime health advisory for PFOA of 70 ppt to address long-term exposure to PFOA. In January 2017, the 2009 Order was amended (“2017 Order”) to incorporate the new lifetime health advisory; the 2017 Amendment requires that DuPont and Chemours provide alternate water or treatment to any public or private drinking water supply in the sampling area with sampling results over 70 ppt and monitor water supplies for four consecutive quarters if sampling results are between 50 ppt-70 ppt. Additionally, the 2017 Amendment reflects changes to Washington Works Facility ownership from DuPont to Chemours, as well as the corporate reorganization between the two companies.

These settlements are part of EPA’s ongoing efforts to compel major PFAS manufacturers to characterize and control ongoing releases from their facilities.

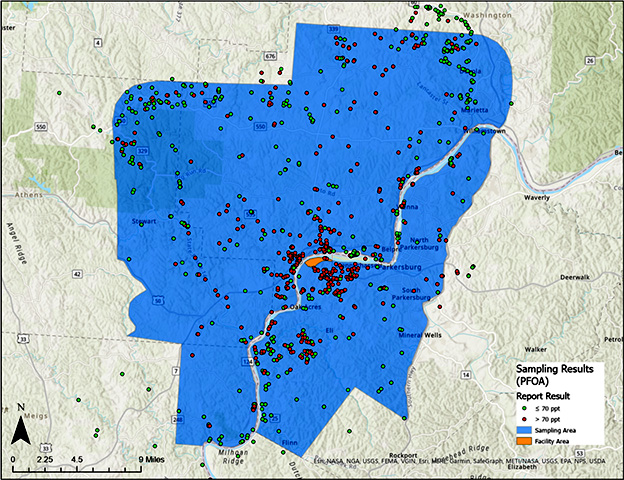

Current Sampling Results for PFOA

As of September 2023, pursuant to the EPA SDWA Orders, Chemours and DuPont have sampled 835 residential drinking water wells; 350 residential drinking water wells had concentrations greater than 70 ppt and have been offered alternate drinking water, including granular activated carbon (GAC) treatment, connection to a public water system (PWS), or permanent bottled water. The remaining 485 residential drinking water wells had concentrations of PFOA less than 70 ppt.

Additionally, as of September 2023, Chemours has also sampled 27 PWSs for PFOA; 12 PWSs had finished water concentrations above 70 ppt and are receiving GAC treatment.

Historic Sampling Results for PFOA

The geographic sampling area, as agreed to under the 2017 Order, includes portions of West Virginia and Ohio. The farthest extent of the sampling area is approximately 20 miles northeast of the Facility. Chemours and DuPont are required to offer to sample public and private water supplies and offer alternate water to locations with PFOA concentrations above 70 ppt to locations within the geographic area shown below:

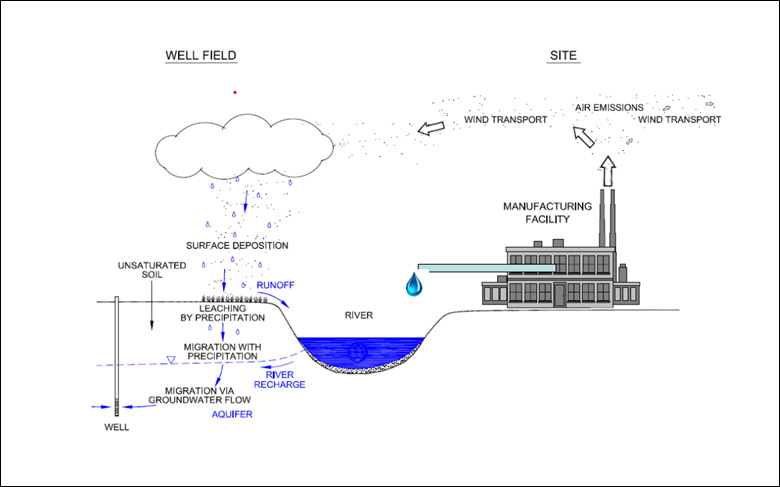

PFAS Pathways

The schematic demonstrates how PFAS can be released from a facility through air emissions and deposited onto surface soils; precipitation events can then cause PFAS molecules to travel through soils to the underlying groundwater, which may be used as a source of drinking water. Similarly, when PFAS is disposed of in unlined landfills, PFAS may eventually leach through the landfill into any underlying groundwater.

The schematic also demonstrates how a facility can discharge PFAS into surface water bodies, like a river, which may be used as a source of drinking water. Depending on conditions of the area, surface water contaminated with PFAS can seep into the ground and “recharge,” or refill, the aquifer or groundwater. Similarly, groundwater contaminated with PFAS can discharge back to the surface to refill nearby surface water bodies, such as, rivers and streams. Additionally, any PFAS released through air emissions and deposited on soil can travel to surface water bodies as runoff during precipitation events, potentially impacting surface and groundwaters.

Evolving PFAS Research and Health Impacts

Studies performed have determined that certain PFAS, including PFOA, in sufficient dosages, can be toxic to animals through ingestion, inhalation and dermal contact. EPA has found that epidemiological studies in human populations and experimental animal studies show correlations between exposures to certain PFAS and an array of cancer and noncancer health effects, including susceptible subpopulations (e.g., early developmental life stages and women of child-bearing age).

Studies involving humans and animals have shown that certain PFAS, including PFOA, can bioaccumulate in the body (e.g., serum half-lives from months to years in humans and monkeys; hours to days/months in rodents). Because PFOA can remain in the body for a long time, drinking water that contains PFOA can, over time, produce concentrations of PFOA in blood serum that are higher than the concentrations present in the water itself.

On June 15, 2022, EPA issued interim updated drinking water health advisories for PFOA and PFOS that supersede those EPA issued in 2016. The interim advisory levels indicate that some negative health effects may occur with concentrations of PFOA or PFOS in water that are near zero. At the same time, EPA issued final health advisories for HFPO-DA. Drinking water health advisories provide information on contaminants that can cause health effects and are known or anticipated to occur in drinking water. EPA health advisories are nonregulatory at the federal level and reflect EPA’s assessment of the best available peer-reviewed science.

On March 14, 2023, EPA announced the proposed National Primary Drinking Water Regulation (“NPDWR”) for six PFAS, including PFOA and HFPO-DA. The proposed PFAS NPDWR does not require any actions until it is finalized. EPA anticipates finalizing the regulation by the end of 2023. EPA expects that if fully implemented, the rule may prevent tens of thousands of serious PFAS-attributable illnesses.