Climate Change Connections: Wyoming (Yellowstone National Park)

Climate change is impacting all regions and sectors of the United States. The State and Regional Climate Change Connections resource highlights climate change connections to culturally, ecologically, or economically important features of each state and territory. The content on this page provides an illustrative example. As climate change will affect each state and territory in diverse ways, this resource only describes a small portion of these risks. For more comprehensive information about regional climate impacts, please visit the Fifth National Climate Assessment and Climate Change Impacts by Sector.

On this page:

Introduction: The World’s First National Park Holds Ecological, Cultural, and Economic Importance

In 1872, Yellowstone became the first national park in North America.1 Federal legislation set aside more than 2 million acres of land “for the benefit and enjoyment of the people,” setting a new precedent of national responsibility to preserve wilderness for public benefit and future generations.2 Today, Yellowstone National Park and the surrounding Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem is considered one of the largest remaining nearly intact temperate ecosystems.3 There are 27 Tribes with historic, spiritual, and cultural connections to the lands and resources now located in Yellowstone National Park.4 These Indigenous communities depend on the region’s water resources and fish and wildlife, and Tribal representatives offer perspectives on park management decisions.2

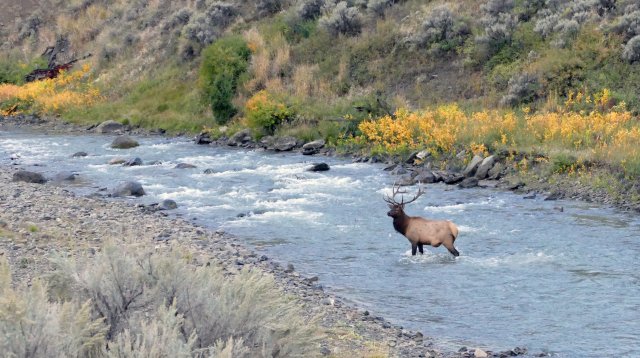

Yellowstone is well known for its biodiversity. The park boasts the largest concentration of mammals in the contiguous United States, with 67 species.5 This includes the largest free-roaming bison herd in the United States, one of the largest elk herds in North America, and one of the only grizzly bear populations in the lower 48 states.3 Three hundred species of birds have been recorded in Yellowstone,6 as well as 12 species of native fish,7 five species of amphibians,8 and six species of reptiles.9 Yellowstone also has an abundance of diverse vegetation, with more than 1,100 plant species, including wildflowers, trees, shrubs, and grasses.10 Three plant species are found only in Yellowstone: Ross’s bentgrass, Yellowstone sand verbena, and Yellowstone sulfur wild buckwheat.10

Millions of visitors come to experience Yellowstone’s natural wonders each year. In recent years, Yellowstone has averaged between 3 million and 4 million visitors annually.11 Recreational visitors to Yellowstone and the nearby Grand Teton National Park contribute significantly to Wyoming’s state economy and support thousands of jobs.12 In 2023, over 7 million visitors were estimated to have spent over $1 billion—primarily on lodging and restaurants—in local areas while visiting U.S. National Park Service (NPS) lands in Wyoming.12

Climate Impacts: Warming Temperatures and Precipitation Changes Can Disrupt Cycles in the Park

Rising temperatures are being documented in Yellowstone National Park and the surrounding area.13,14 Since 1950, annual average temperatures in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem have increased by over 2°F.14 This warming is expected to accelerate throughout this century, with temperatures projected to be 5°F to 10°F warmer by 2100 compared with the period from 1986 to 2005.14 Projections also show an increase in the number of very hot days (with high temperatures over 90°F) and a decrease in the number of cold days (with low temperatures below 32°F).14

While average precipitation in the Greater Yellowstone Area has not changed significantly since 1950, seasonal patterns have shifted.14 Throughout Wyoming, winter and spring precipitation is expected to increase with climate change.15 In a warming climate, more precipitation will be expected to fall as rain instead of snow in most areas reducing the extent and depth of snowpack. Snowfall has already decreased significantly in recent decades, and researchers expect the area to see a 40 percent loss in snowpack by the end of the century compared with the period from 1986 to 2005.14 Snow is also projected to melt earlier in the spring, leading to drier conditions in summer months.

Annual water cycles in the Greater Yellowstone Area are driven by snow accumulating during colder months and melting in the spring and summer.14 In the western United States, most stream water comes from snowmelt. Yellowstone’s watersheds feed into the Colorado, Columbia, and Missouri Rivers.16 Decreases in snowpack and earlier snowmelt in the region will have far-reaching consequences for water availability for drinking, agriculture, recreation, and energy production.17,18

Warming temperatures and changing precipitation patterns are likely to alter the composition and distribution of Yellowstone’s native species. For example, increasing drought conditions can stress and even kill plant populations. Warming also creates conditions favorable to pests such as bark beetles, which can damage and kill trees.19 Trees already stressed by heat, drought, and wildfire will be more susceptible to pests. Changing seasonal patterns are expected to influence the timing of vegetation growth, which can affect food availability and migration patterns for birds and mammals.16 These impacts could also hinder recreational activities such as fishing and wildlife viewing and negatively impact the economies and jobs that depend on them. Reduced streamflow and warmer stream temperatures are affecting fish populations in the region. In August 2016, large fish die-offs and closures of part of the Yellowstone River were attributed to warm temperatures.20 In addition to affecting species, warmer winters and decreased snow cover could also significantly shorten the season for winter activities such as skiing.20

Wildfires have shaped the Greater Yellowstone Area’s unique and biodiverse ecosystem. Over time, many plants have adapted to survive or even benefit from fires, so periodic fires help maintain the ecosystem’s overall health.21 However, higher temperatures and drought conditions have caused larger fires to happen more often. Studies have found that climate change has already lengthened the fire season and made fires more frequent and severe while increasing the number of acres burned per year.22 Smoke exposure from wildfires can be detrimental to human health. Studies have found that visits to Yellowstone National Park and other public lands in the western United States declined during years when fires occurred, leading to economic losses for the region.23,24

Taking Action: Promoting Research and Outreach in Yellowstone National Park

Addressing climate change requires reducing greenhouse gas emissions while preparing for and protecting against current and future climate impacts. Communities, public officials, and individuals in every part of the United States can continue to explore and implement climate adaptation and mitigation measures. Environmental managers and the NPS are taking steps to prepare for a changing climate, including:

- Monitoring and research. Groups like the Greater Yellowstone Inventory and Monitoring Network have collected data for many decades to monitor plants, animals, and the broader environment with the goal of evaluating overall park health over time.25 The NPS Climate Change Response Program also organizes efforts to better understand the impacts of climate change on national parks. Ongoing research efforts will help park managers and regional stakeholders respond to climate impacts and maintain the area’s unique natural and cultural resources for public enjoyment for many years to come.26

- Education and outreach. Yellowstone National Park offers resources to educate the public about climate change science and impacts on the park. These resources include efforts by park rangers to engage with visitors about climate impacts and broader sustainability efforts at Yellowstone, as well as online tools that allow users to explore historical climate data and projected changes within the Greater Yellowstone Area.27 The park is also undertaking conservation and energy reduction measures in their operations, modeling mitigation strategies.28

To learn more about climate change impacts in Wyoming and the Northern Great Plains region, see Chapter 25 of the Fifth National Climate Assessment.

Related Resources

- EPA Climate Change Indicators: Seasonal Temperature

- EPA Climate Change Indicators: Snowpack

- EPA Climate Change Indicators: Snow Cover

- Changes in Yellowstone Climate (NPS)

- Climate Change—Yellowstone National Park (NPS)

- Examining the Evidence: Climate Change (NPS)

- Greater Yellowstone Area Climate Change Explorer (NPS)

- Greater Yellowstone Climate Assessment (U.S. Geological Survey Northern Rocky Mountain Science Center)

- Wyoming State Climate Summary 2022 (NOAA)

References

1 National Park Service. (n.d.). The world’s first national park. Yellowstone National Park. Retrieved December 19, 2023, from https://www.nps.gov/yell/index.htm

2 National Park Service. (n.d.). Modern management. Yellowstone National Park. Retrieved July 25, 2023, from https://www.nps.gov/yell/learn/historyculture/modernmanagement.htm

3 National Park Service. (n.d.). Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. Yellowstone National Park. Retrieved July 25, 2023, from https://www.nps.gov/yell/learn/nature/greater-yellowstone-ecosystem.htm

4 National Park Service. (n.d.). Historic Tribes. Yellowstone National Park. Retrieved January 23, 2024, from https://www.nps.gov/yell/learn/historyculture/historic-tribes.htm

5 National Park Service. (n.d.). Mammals. Yellowstone National Park. Retrieved July 25, 2023, from https://www.nps.gov/yell/learn/nature/mammals.htm

6 National Park Service. (n.d.). Birds. Yellowstone National Park. Retrieved July 25, 2023, from https://www.nps.gov/yell/learn/nature/birds.htm

7 National Park Service. (n.d.). Fish ecology. Yellowstone National Park. Retrieved June 21, 2024, from https://www.nps.gov/yell/learn/nature/fish-ecology.htm

8 National Park Service. (n.d.). Amphibians. Yellowstone National Park. Retrieved July 25, 2023, from https://www.nps.gov/yell/learn/nature/amphibians.htm

9 National Park Service. (n.d.). Reptiles. Yellowstone National Park. Retrieved July 25, 2023, from https://www.nps.gov/yell/learn/nature/reptiles.htm

10 National Park Service. (n.d.). Plants. Yellowstone National Park. Retrieved July 25, 2023, from https://www.nps.gov/yell/learn/nature/plants.htm

11 National Park Service. (n.d.). Annual park ranking report for recreation visits. Retrieved July 25, 2023, from https://irma.nps.gov/Stats/SSRSReports/Park%20Specific%20Reports/Annual%20Park%20Recreation%20Visitation%20Graph%20(1904%20-%20Last%20Calendar%20Year)?Park=YELL

12 Flyr, M., & Koontz, L. (2024). 2023 National Park Service visitor spending effects: Economic contributions to local communities, states, and the nation (Science Report NPS/SR—2024/174). National Park Service, Environmental Quality Division. https://www.nps.gov/subjects/socialscience/vse.htm

13 EPA. (2024). Climate change indicators: U.S. and global temperature. Retrieved June 18, 2024, from https://www.epa.gov/climate-indicators/climate-change-indicators-us-and-global-temperature

14 Hostetler, S. W., Whitlock, C., Shuman, B., Liefert, D., Wolf Drimal, C., & Bischke, S. (2021). Greater Yellowstone climate assessment: Past, present, and future climate change in greater Yellowstone watersheds. In J. R. Adler & G. T. Pederson (Eds.), Greater Yellowstone Climate Assessment. Montana State University. https://doi.org/10.15788/GYCA2021

15 Frankson, R., Kunkel, K. E., Stevens, L. E., Easterling, D. R., Stewart, B. C., Umphlett, N. A., & Stiles, C. J. (2022). Wyoming state climate summary 2022 (NOAA Technical Report NESDIS 150-WY). NOAA National Environmental Satellite, Data, and Information Service. https://statesummaries.ncics.org/chapter/wy

16 National Park Service. (n.d.). Changes in Yellowstone climate. Yellowstone National Park. Retrieved December 8, 2023, from https://www.nps.gov/yell/learn/nature/changes-in-yellowstone-climate.htm

17 Chang, M., Erikson, L., Araújo, K., Asinas, E. N., Chisholm Hatfield, S., Crozier, L. G., Fleishman, E., Greene, C. S., Grossman, E. E., Luce, C., Paudel, J., Rajagopalan, K., Rasmussen, E., Raymond, C., Reyes, J. J., & Shandas, V. (2023). Ch. 27. Northwest. In A. R. Crimmins, C. W. Avery, D. R. Easterling, K. E. Kunkel, B. C. Stewart, & T. K. Maycock (Eds.), Fifth National Climate Assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program. https://doi.org/10.7930/NCA5.2023.CH27

18 Payton, E. A., Pinson, A. O., Asefa, T., Condon, L. E., Dupigny-Giroux, L.-A. L., Harding, B. L., Kiang, J., Lee, D. H., McAfee, S. A., Pflug, J. M., Rangwala, I., Tanana, H. J., & Wright, D. B. (2023). Ch. 4. Water. In A. R. Crimmins, C. W. Avery, D. R. Easterling, K. E. Kunkel, B. C. Stewart, & T. K. Maycock (Eds.), Fifth National Climate Assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program. https://doi.org/10.7930/NCA5.2023.CH4

19 Buotte, P. C., Hicke, J. A., Preisler, H. K., Abatzoglou, J. T., Raffa, K. F., & Logan, J. A. (2016). Climate influences on whitebark pine mortality from mountain pine beetle in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. Ecological Applications, 26(8), 2507–2524. https://doi.org/10.1002/eap.1396

20 Knapp, C. N., Kluck, D. R., Guntenspergen, G., Ahlering, M. A., Aimone, N. M., Bamzai-Dodson, A., Basche, A., Byron, R. G., Conroy-Ben, O., Haggerty, M. N., Haigh, T. R., Johnson, C., Mayes Boustead, B., Mueller, N. D., Ott, J. P., Paige, G. B., Ryberg, K. R., Schuurman, G. W., & Tangen, S. G. (2023). Ch. 25. Northern Great Plains. In A. R. Crimmins, C. W. Avery, D. R. Easterling, K. E. Kunkel, B. C. Stewart, & T. K. Maycock (Eds.), Fifth National Climate Assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program. https://doi.org/10.7930/NCA5.2023.CH25

21 National Park Service. (n.d.). Fire. Yellowstone National Park. Retrieved July 25, 2023, from https://www.nps.gov/yell/learn/nature/fire.htm

22 EPA. (2024). Climate change indicators: Wildfires. Retrieved February 20, 2024, from https://www.epa.gov/climate-indicators/climate-change-indicators-wildfires

23 Gellman, J., Walls, M., & Wibbenmeyer, M. (2022). Wildfire, smoke, and outdoor recreation in the western United States. Forest Policy and Economics, 134, 102619. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forpol.2021.102619

24 Duffield, J. W., Neher, C. J., Patterson, D. A., & Deskins, A. M. (2013). Effects of wildfire on national park visitation and the regional economy: A natural experiment in the Northern Rockies. International Journal of Wildland Fire, 22, 1155–1166. http://dx.doi.org/10.1071/WF12170

25 National Park Service. (n.d.). Natural resource monitoring at Yellowstone National Park. Greater Yellowstone Inventory & Monitoring Network. Retrieved July 25, 2023, from https://www.nps.gov/im/gryn/yell.htm

26 National Park Service. (2019). National Park Service Climate Change Response Program: Strategic plan. U.S. Department of the Interior. https://www.nps.gov/orgs/ccrp/upload/CCRP-Strategic-plan-508-smaller.pdf

27 National Park Service. (n.d.). Examining the evidence: Climate change. Yellowstone National Park. Retrieved July 25, 2023, from https://www.nps.gov/yell/learn/nature/climate-examine-evidence.htm

28 National Park Service. (n.d.). Conservation measures. Yellowstone National Park. Retrieved June 11, 2024, from https://www.nps.gov/yell/getinvolved/conservation-measures.htm